Download Publication

Sanjeewa Singhabahu, Chathura Wijesinghe, Dilini Gunawardana, Muditha D. Senarath-Yapa, Madushani Kannangara, Roshani Edirisinghe, Vajira H.W. Dissanayake

URI:

DOI: 10.4172/2375-4338.1000177

Journal Name: Journal of Rice Research

1Human Genetics Unit, University of Colombo, Kynsey Road, Colombo-00800, Sri Lanka

2John Keells Research, No. 525/1 Union Place, Colombo-00200, Sri LankaCorresponding Author:Vajira H.W. Dissanayake

Human Genetics Unit, Faculty of Medicine

University of Colombo, Kynsey Road

Colombo-00800, Sri Lanka

Tel: +94 (0)11 2 689545

Fax: +94 (0)11 2 689545

E-mail: vajirahwd@hotmail.com

Received Date: January 21, 2017; Accepted Date: March 12, 2017; Published Date: March 20, 2017

Citation: Singhabahu S, Wijesinghe C, Gunawardana D, Senerath-Yapa MD, Kannangara M, et al. (2017) Whole Genome Sequencing and Analysis of Godawee, a Salt Tolerant Indica Rice Variety. J Rice Res 5:177. doi:10.4172/2375-4338.1000177

Copyright: © 2017 Singhabahu S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Rice Research: Open Access

Abstract

Godawee is a cultivated salt tolerant Oryza sativa rice variety indigenous to Sri Lanka, but its genetic basis is unknown. The whole genome of Godawee was sequenced using Illumina paired-end technology. The reads were mapped to Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome. Investigation of genome wide variation patterns resulted in the identification of 2,231,717 SNPs and 480,460 InDels. In silico analysis identified 192,249 non-synonymous SNPs in 31,287 genes. Variants in 28 Salt Tolerance Related Genes (STRGs) were examined. The OsHKT 2;1 gene had the largest number of SNPs in comparison to the reference genome. 16 non-synonymous SNPs that were predicted to have functional effects either by SIFT, Provean or SNAP algorithms were detected in the STRGs. The upstream regions of the STRGs were examined for cis-regulatory elements found in STIFDB, Plant CARE and PLACE databases. The most striking of this was the WRKY cis-acting family of elements which were found in abundance in the upstream regions of OsAPx8, OsMSR2, OsTIR1, OsHKT2;3, OsHKT14 and OsSOS1 genes. Sequencing and whole genome analysis of Godawee helped to understand the genetic basis of its salinity tolerance which is a complex trait involving multiple factors.

Keywords

NGS; Genomics; Rice; Oryza; Abiotic stress; Salinity tolerance; Whole genome

Introduction

Rice has been consumed in tropical and subtropical Asia from as far back as 8000 BC [1]. Over the years the process of farming and selection for specific features has changed the wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, consumed by ancient people into the improved species, Oryza sativa, which is the major staple food of a third of the world population today [2].

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) estimates that the world population would reach 9.6 billion by the year 2050 [3]. To ensure food security for this increasing population food production has to increase by approximately 44 million metric tons annually from now on. Unpredictable climate change and abiotic stresses such as soil water scarcity (drought) and salinity hamper achieving this goal [4–8].

Accumulation of water-soluble salts in the soil is high in arid and semi-arid regions. No part of the world however is safe from salinization [9]. Soil that has an electrical conductivity of >4 dS m-1 is considered to be saline soil [10]. The osmotic effect of saline water reduces the uptake of water by plants. The excess ions adversely affect plant cells by efflux of intracellular water. Salinity is also known to increase the nutritional imbalance in plants [11]. These mechanisms play a major role in inhibiting plant growth [12].

Rice is the most sensitive cereal crop for salinity [13]. The loss of rice yield in saline lands is estimated to be 30-50% per annum [14]. During evolution plants have developed mechanisms to sense changes in the environment and adapt to them [15]. Rice has also developed mechanisms to withstand salinity [16]. People have selected and cultivated such salt tolerant rice varieties from time immemorial.

There are three common techniques that are used to produce rice plants that can tolerate salinity. They are conventional breeding; identification of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and marker assisted selection or direct screening of rice plants in a saline environment [17,18]; and genetic modification by introducing Salt Tolerance Related Genes (STRGs). The recently introduced technique of targeted gene editing promises great potential for the alteration of genes without affecting characteristics of elite genotypes [19–22]. Genetic modification requires the identification of the relevant genes in stress tolerant pathways and genetic variants in those genes that confer functional advantage. Whole genome sequencing of plants on next generation genome sequencing platforms makes it possible to do this faster and more efficiently than before [23].

Godawee, a Sri Lankan traditional rice variety known for its salinity tolerance [24,25], was sequenced as the initial step of a whole genomebased polymorphism study to identify genes involved in salinity tolerance and genetic variants in those genes that confer functional advantage. In this paper we report the initial results of this work.

Materials and Methods

Sampling and DNA extraction

Plants of Oryza sativa L. cv. Godawee (Plant Genetic Resource Centre (PGRC), Peradeniya, Sri Lanka Accession Number: 006182) were obtained from the Rice Research and Development Institute, Batalagoda, Sri Lanka. The samples had been grown under controlled conditions. The nuclear DNA of Godawee was isolated from young leaves using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) as mentioned in the manufacturer’s protocol.

Sequence and assembly

Library construction and sequencing: A paired-end sequencing library with inserts of approximately 600 bp in size was constructed using 50ng of genomic DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a Nextera sample preparation kit (Illumina Inc., USA). Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to confirm the fragment sizes of the library. Approximately 15 pg of the DNA library was denatured using freshly prepared 0.2N NaOH and sequencing was performed using the TruSeq v3 kit (Illumina Inc., USA) on a Miseq platform. The initial cluster density was 1548 K/mm2. At the end of a 55-hour long sequencing run 18773.7 MB of sequencing reads were produced. All reads passed the Illumina quality filter. Of these reads 11500 MB (54 million sequencing reads) were of high quality (above Q30). The reads were obtained in FASTQ file format for further analysis.

Reads mapping: Nextera DNA adapter trimmed reads generated on the Illumina Miseq platform were trimmed to remove low quality bases and filtered using ‘Trimmomatic’ (http://www.usadellab.org/cms/?page=trimmomatic/) by retaining the bases with a minimum Phred quality score of 30. Burrows Wheeler alignment (BWA) tool [26] with default parameters was used for alignment of all the quality filtered paired end reads to Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare reference genome – the unified build release Os-Nipponbare-Reference- IRGSP-5.0 (International Rice Genome Sequencing Project). BWA aligner tool [26] with default parameters was also used to map reads to chloroplast (DDBJ Acc. No: X15901) and mitochondrial (DDBJ Acc. No: DQ167400) genome references.

The sequences that did not map to the Nipponbare reference genome were assembled into contigs using the ABySS tool with default parameters [27,28]. Contigs larger than 1000 bp were filtered and Blasted against the Oryza sativa japonica reference genome to identify the divergent homologs in the Godawee genome followed by annotation using Blast2GO software through Blastn analysis against the NCBI nucleotide database [29,30].

Variants identification and annotation

The aligned reads in the SAM file was converted to BAM and sorted using Sort of SAMtools V0.1.19 [31]. PCR duplicates were removed using the Picard tools V0.1.19 (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). The GATK tool [32] was used with default parameters for variant calling followed by identification of SNPs and InDels.

The variant calling file (VCF) was filtered using parameters such as mapping quality ≥ 55, base quality ≥ 30, variant quality ≥ 90, number of reads per base between 5 and 75 and the distance of adjacent variants ≥ 5. The rice7 gene model database for Oryza sativa (http://sourceforge.net/projects/snpeff/files/databases/v3_6/snpEff_v3_6_rice7.zip) and SnpEff V3.6 tools were used to annotate the filtered variants [33].

SNPs and InDels were annotated as genic and intergenic. The SNPs were separated on the basis of transition (C/T and G/A) and transversion (C/G, T/A, A/C and G/T). Further classification of SNPs and InDels found in the genic region was carried out on the basis of their location (i.e. exons, introns, 5’UTRs, 3’UTRs, and splice-site regions). SNPs in coding region were also classified into synonymous (cause no change in amino acid), non-synonymous (cause change in amino acid), stop gain (introduce a stop codon), stop loss (remove existing stop codon), start gain (introduce a start codon), and start loss (remove existing start codon).

Densities of SNPs and InDels in every 100 kb region were calculated to locate hyper- and hypo-variable regions of the genome. Chromosome regions containing SNPs/kb>5 or InDels/kb>1 were defined as hyper- variable regions whereas those containing SNPs/ kb<0.1 or InDels/kb<0.01 were defined as hypo-variable regions.

Analysis of the variants in the salt tolerance related genes (STRGs) and functional effects of non-synonymous SNPs

SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/) [34], Provean (http://provean.jcvi.org) [35] and SNAP (https://rostlab.org/services/snap/) [36] algorithms were used to determine the functional effect of non-synonymous SNPs.

Analysis of cis acting regulatory elements (CARE) of salt tolerance related genes (STRGs)

5’ upstream regions (2.0 kbp) of each STRGs were extracted from the Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare reference genome. The extracted sequences were altered according to the variants present in the Godawee genome using the GATK tool (FastaAlternateReferenceMarker-FARM). These altered sequences were compared with the unchanged Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare reference genome for cis-regulatory elements found in scientific literature and also registered in STIFDB (http://caps.ncbs.res.in/stifdb2/) [37], Plant CARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) [38] and PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/htdocs/PLACE/) [39] tools.

Results

Next generation sequencing (NGS) and mapping

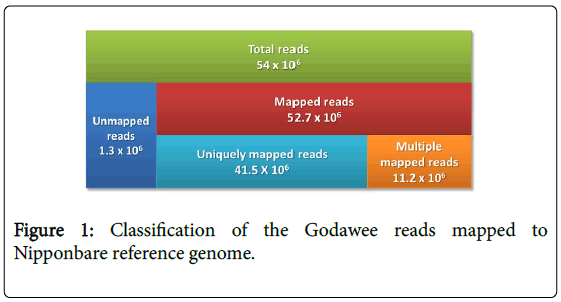

Whole genome sequencing of Godawee generated 11.5 GB of extremely high quality sequence data (54 million sequencing reads). Phred quality score of more than 90% of the reads was >30. These reads were first mapped to Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare reference genome using the Burrows Wheeler Alignment (BWA) Tool [26]. The overall mapping rate was 0.97 (52.7 × 106 reads). The depth of coverage was 22x. The reads covered 91.65% of the reference genome after duplicate masking (Figure 1). Majority of the mapped reads (78.7%=41.5 × 106 reads) were uniquely mapped to chromosomes. The remainder mapped to multiple locations on the reference genome (Figure 1). Unmapped reads (1.3 × 106) were de novo assembled (described later).

Figure 1: Classification of the Godawee reads mapped to Nipponbare reference genome.

Variant identification

The SNPs and InDels in O. sativa L. cv. Godawee were determined with reference to the Nipponbare reference genome. A total of 4,334,404 variants (3,747,311 SNPs and 587,093 InDels) were identified prior to quality filtering. Quality filtering yielded 2,231,717 SNPs and 480,460 InDels (235,905 insertions and 244,555 deletions). Homozygous to heterozygous variant ratios were calculated to be 5.27 for SNPs and 4.65 for InDels. The highest total number of variants was on chromosome 1 (316,158) and the lowest number was on chromosome 9 (171,807). Average number of variants per chromosome was 226,015 at the rate of one variant for every 138 bases (Table 1).

| Chromosome | Chromosome Length of Nipponbare Genome (bp) | SNPs | InDels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Density (SNPs/100kb) | Number | Density (InDels/100kb) | ||

| 1 | 43270923 | 257826 | 595.4 | 58332 | 134.7 |

| 2 | 35937250 | 215592 | 598.9 | 47334 | 131.5 |

| 3 | 36413819 | 211420 | 579.2 | 47207 | 129.3 |

| 4 | 35502694 | 188239 | 528.8 | 40530 | 113.8 |

| 5 | 29958434 | 152830 | 509.4 | 32565 | 108.6 |

| 6 | 31248787 | 190097 | 607.3 | 39683 | 126.8 |

| 7 | 29697621 | 187399 | 631 | 39637 | 133.5 |

| 8 | 28443022 | 164529 | 577.3 | 35323 | 123.9 |

| 9 | 23012720 | 142257 | 615.8 | 29550 | 127.9 |

| 10 | 23207287 | 161257 | 692.1 | 32777 | 141.3 |

| 11 | 29021106 | 200575 | 689.3 | 41676 | 143.2 |

| 12 | 27531856 | 159696 | 578.6 | 35846 | 129.9 |

| Total | 373245519 | 2231717 | 600.3 | 480460 | 128.7007 |

Table 1: Number and density of SNPs and InDels in the Godawee genome.

The density of occurrence of variants was calculated to determine the genomic distribution of SNPs and InDels. The highest SNP density was on chromosome 10 (692.1 per 100 kb) and the lowest density was on chromosome 5 (509.4 per 100 kb). The highest InDel density was on chromosome 11 (143.2 per 100 kb) and the lowest was on chromosome 5 (108.6 per 100 kb) (Table 1). The average density of variants across the genome was 600.3 SNPs per 100 kb and 128.7 InDels per 100 kb. The genome comprised of 2485 high SNP density regions (SNP/kb>5) and 22 low SNP density regions (SNP/kb<0.1). Chromosome 1 harboured the highest number of high SNP density regions (308) and chromosome 9 harboured the lowest number of high SNP density regions (160) (Table 2). In comparison, the genome only contained 3 high InDel density regions (InDel/kb>5) and 90 low InDel density regions (InDel/kb<0.1). The highest numbers of low InDel density regions were detected in chromosome 5.

| Chromosome | SNP density | InDel density | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | |

| 1 | 308 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 243 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 3 | 243 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 4 | 198 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| 5 | 163 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

| 6 | 210 | 5 | 0 | 8 |

| 7 | 217 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 8 | 183 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| 9 | 160 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 10 | 184 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 11 | 216 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| 12 | 160 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 2485 | 22 | 3 | 90 |

Table 2: Number of high and low SNP and InDel density regions in chromosomes.

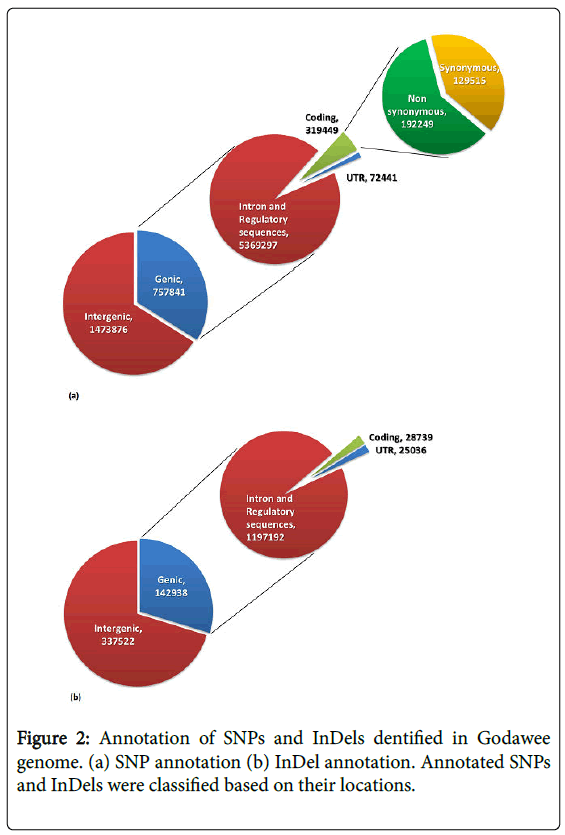

Annotation of variants

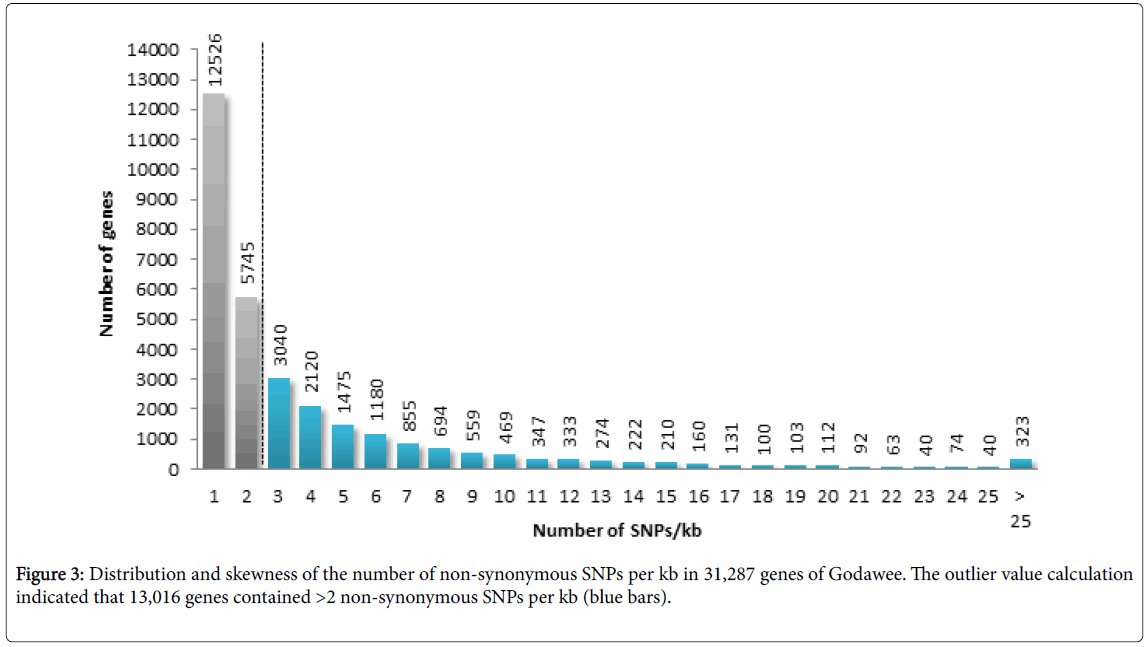

Analysis of SNPs showed that 757,841 were genic and 1,473,876 were intergenic (Figure 2a). Among the SNPs found in genic regions 129,515 (40.25%) were synonymous variants (silent variants) and 192,249 (59.75%) were non-synonymous variants. Among nonsynonymous variants 186,054 (57.82%) were missence variants and 6,195 (1.93%) were nonsense variants. Non-synonymous variants were found to be distributed over 31,287 genes and the SNP number varied between 1 to 241 SNPs per gene. In the genic regions the number of SNPs/kb ranged between 0.03 and 87.61. The transition to transversion ratio of SNPs ranged between 2.26 in chromosome 4 and 2.54 in chromosome 3 with an average of 2.41. Outliers of non-synonymous SNPs/kb in genic regions was calculated using Z-score and 13,016 genes were classified as outliers due to the presence of more than 2 non-synonymous SNPs/kb (Figure 3). Analysis of InDels showed that 142,938 were genic and 337,522 were intergenic. Further analysis showed that 28,739 InDels were in coding regions (Figure 2b). The majority of InDels were either mono-nucleotide (43.18%) or dinucleotide (17.07%). InDels with lengths ranging from -203 to +375 bp were detected.

Figure 2: Annotation of SNPs and InDels dentified in Godawee genome. (a) SNP annotation (b) InDel annotation. Annotated SNPs and InDels were classified based on their locations.

Figure 3: Distribution and skewness of the number of non-synonymous SNPs per kb in 31,287 genes of Godawee. The outlier value calculation indicated that 13,016 genes contained >2 non-synonymous SNPs per kb (blue bars).

Analysis of the variants in the salt tolerance related genes (STRGs) and functional effects of non-synonymous SNPs

Salt tolerant genes were identified by searching scientific literature and by examining gene expression data of the NCBI GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Salt tolerant pathways are known to consist of approximately 28 Salt Tolerance Related Genes (STRGs) (Table 3). Analysis of these genes showed the presence of 2249 SNPs and 632 InDels. The majority of SNPs and InDels were in introns and other non-coding regions. The coding regions contained 78 nonsynonymous SNPs and 76 synonymous SNPs (Table 3). Nonsynonymous SNPs ranged from 1 (OsNAC6, OsMAPK4, OsAPx8, OsMAPK5, OsAFB2, OsSIK1, OsHKT1;4 and OsNAC) to a maximum of 32 (OsHKT2;1) per gene. Non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous SNP (Ks) ratio can be calculated to investigate positive (Ka/Ks>1), negative (Ka/Ks<1) or neutral (Ka/Ks=1) evolutionary selection of the genes. The Ka/Ks ratio showed 6 STRGs under positive selection, 7 STRGs under negative selection and 4 STRGs under neutral selection (Table 3).

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | Non-Coding SNPs | Non-Synonymous SNPs (Ka) | Synonymous SNPs (Ks) | Ka/Ks | Non-coding InDels | Coding InDels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsNAC6 | OsNAC6 | 126 | 1 | 0 | – | 40 | 0 |

| OsMSR2 | OsMSR2 | 95 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 25 | 0 |

| OsMAPK4 | OsMAPK4 | 27 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 6 | 0 |

| OsAPx8 | OsAPx8 | 83 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 0 |

| OsMAPK5 | OsMAPK5 | 73 | 1 | 0 | – | 12 | 0 |

| OsAFB2 | OsAFB2 | 96 | 1 | 3 | 0.3333 | 26 | 0 |

| OsCPK12 | OsCPK12 | 55 | 0 | 0 | – | 9 | 0 |

| OsCDPK7 | OsCDPK7 | 59 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| OsTIR1 | OsTIR1 | 75 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| OsCBL4 | OsCBL4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | – | 16 | 0 |

| OsLEA3 | OsLEA3 | 80 | 3 | 0 | – | 25 | 0 |

| OsMAPK44 | OsMAPK44 | 70 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| OsSIK1 | Os06g03970 | 57 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 20 | 0 |

| OsCIPK24 | OsCIPK24 | 49 | 2 | 3 | 0.6667 | 19 | 0 |

| OsMSRMK3 | OsMSRMK3 | 66 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| OsHKT2;1 | OsHKT2;1 | 64 | 32 | 36 | 0.8889 | 22 | 0 |

| OsHKT2;3 | OsHKT2;3 | 57 | 5 | 2 | 2.5 | 27 | 1 |

| OsHKT2;4 | OsHKT2;4 | 141 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 33 | 0 |

| OsHKT1;1 | OsHKT1;1 | 70 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 39 | 1 |

| OsHKT1;3 | OsHKT1;3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | – | 16 | 0 |

| OsHKT1;4 | OsHKT1;4 | 58 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 13 | 0 |

| OsHKT1;5 | OsHKT1;5 | 115 | 4 | 3 | 1.3334 | 25 | 0 |

| OsNAC | OsNAC | 87 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 28 | 0 |

| OsNHX | OsNHX | 83 | 0 | 0 | – | 33 | 0 |

| OsrbohB | OsrbohB | 115 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 39 | 1 |

| OsPSY1 | OsPSY1 | 60 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 0 |

| OsEDR1 | OsEDR1 | 68 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| OsSOS1 | OsSOS1 | 106 | 3 | 4 | 0.75 | 34 | 0 |

| Total/ average | 2095 | 78 | 76 | 1.0263 | 628 | 4 |

Table 3: Details of the SNPs and InDels identified in the salt tolerance related genes (STRG).

The summary of prediction of the effect of SNPs on protein function in STRGs is in Table 4. Only two SNPs were found to be deleterious by more than one algorithm. They were OsHKT 2;1 (1312T>C / Phe438Leu) and OsHKT 2;3 (470T>C / Ile157Thr).

| Gene Name | MSU locus | SIFT | SNAP | Provean | Amino acid position | Nucleotide position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsNAC6 | LOC_Os01g66120 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsMSR2 | LOC_Os01g72530 | ND | ND | ND | T 18 A | 52A>G |

| D | ND | ND | T 38 A | 112A>G | ||

| OsMAPK4 | LOC_Os02g05480 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsAPx8 | LOC_Os02g34810 | D | ND | ND | P 377 A | 1129C>G |

| OsMAPK5 | LOC_Os03g17700 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsAFB2 | LOC_Os04g32460 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsCPK12 | LOC_Os04g47300 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsCDPK7 | LOC_Os04g49510 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsTIR1 | LOC_Os05g05800 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsCBL4 | LOC_Os05g45810 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsLEA3 | LOC_Os05g46480 | ND | D | ND | S83G | 247A>G |

| ND | D | ND | E175K | 523G>A | ||

| OsMAPK44 | LOC_Os05g49140 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsSIK1 | LOC_Os06g03970 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsCIPK24 | LOC_Os06g40370 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsMSRMK3 | LOC_Os06g48590 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsHKT2;1 | LOC_Os06g48810 | ND | D | ND | S88G | 262A>G |

| ND | D | ND | C158S | 472T>A | ||

| D | ND | ND | Q 420 R | 1259A>G | ||

| D | ND | ND | I 430 N | 1289T>A | ||

| D | D | ND | F 438 L | 1312T>C | ||

| OsHKT2;3 | LOC_Os01g34850 | D | D | ND | I 157 T | 470T>C |

| OsHKT2;4 | LOC_Os06g48800 | ND | D | ND | S 133 L | 398C>T |

| OsHKT1;1 | LOC_Os04g51820 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsHKT1;3 | LOC_Os02g07830 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsHKT1;4 | LOC_Os04g51830 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsHKT1;5 | LOC_Os01g20160 | ND | D | ND | H332D | 994C>G |

| OsNAC | LOC_Os07g12340 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsNHX | LOC_Os07g47100 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsrbohB | LOC_Os09g26660 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| OsPSY1 | LOC_Os09g38320 | ND | ND | D | D402G | 1205A>G |

| OsEDR1 | LOC_Os10g29540 | ND | D | ND | F655L | 1965C>G |

| ND | D | ND | R500G | 1498A>G | ||

| OsSOS1 | LOC_Os12g44360 | ND | ND | ND |

Table 4: In silico functional analysis of variants in STRGs. D=Deleterious, ND=Non-deleterious.

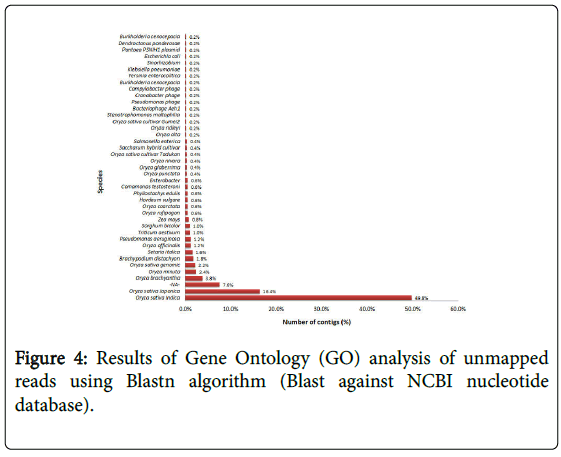

Annotation of unmapped reads

De novo assembly of unmapped reads resulted in 283,020 contigs. Since the average rice gene size is 3223 bp (Rice genome annotation project), the resultant contigs larger than 1000 bp (500 contigs) were selected for further analysis and blasted against the Oryza sativa japonica reference genome to identify the divergent homologs in the Godawee genome. The contigs did not show significant similarity with any sequence in the reference. These contigs were annotated with Blast2GO software using the Blastn algorithm in order to search for matches in the NCBI RefSeq database and annotated with Gene Ontology terms [29,30]. Blast2GO analysis using the Blastn algorithm is summarised in Figure 4. This showed that the majority of the contigs matched Oryza sativa indica sequences (49.8%) or Oryza sativa japonica sequences (16.4%).

Figure 4: Results of Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of unmapped reads using Blastn algorithm (Blast against NCBI nucleotide database).

Analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements (CARE) of salt tolerance related genes (STRGs)

5’ upstream regions (2.0 kbp) of each STRG was evaluated for the presence of putative cis-regulatory elements found in scientific literature and also registered in STIFDB (http://caps.ncbs.res.in/stifdb2/) [37], CARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html) [38] and PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/htdocs/PLACE/) [39] databases.

A total of 10 known CAREs associated with stress responsive pathways were analysed against upstream regions of the 28 STRGs and compared with the Oryza sativa reference genome in order to understand gene regulation.

CAREs involved in WRKY encoded transcriptional repression of gibberellin signalling were observed in high frequencies in the upstream regions of all 28 genes [40]. The number of WRKY CAREs in the upstream region of the OsAP × 8 (Ascorbate peroxidase 8) gene in the Godawee genome, as compared to the reference (Nipponbare), was significantly higher. Furthermore, these were found in higher numbers in OsMSR2, OsTIR1, OsHKT2;3, OsHKT1;4 and OsSOS1 genes in Godawee compared to their counterparts in the reference.

Discussion

In this paper we report the sequencing and analysis of the Godawee genome with special reference to the genes related to salinity tolerance. We generated high quality sequence reads of the Godawee genome and mapped it to the Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare reference genome, and performed a bioinformatic analysis.

The majority of the reads were uniquely mapped with others mapping to multiple locations. The mapping rate obtained was 0.97 with a depth of 22x. The reads covered 91.65% of the reference genome. In agreement with previous reports of similar genome wide studies of other rice varieties 8.35% of the reads did not map to the reference genome [41,42]. Further analysis of the unmapped reads showed that the reads consisted of sequences which mapped to other Oryza sativa subspecies as has been reported previously [43].

Analysis of mapped reads showed that the distribution of SNPs in the Godawee genome was diverse. The number of SNPs in many regions was low indicating that there were SNP deserts as has been reported previously [41,44,45]. A large SNP desert was detected in chromosome 5 between 9.2 and 13.4 Mb with 1.21 SNP/kb. Two more SNP deserts were identified in chromosome 4 (25.3 to 27.3 Mb, 0.91 SNP/kb) and 8 (23.8 to 24.4 Mb, 0.51 SNP/ kb). SNP deserts of 2.1 Mb and 0.7 Mb in size have been reported in monocots by Rathinasabapathi et al., (2015) [41]. The presence of similar SNP deserts in Godawee rice may indicate the highly conserved function of these regions.

The ratio of transition to transversion of SNPs that was found to be 2.427 with a higher number of transition SNPs than transversion SNPs is comparable with the ratios reported previously [44,46,47]. It is hypothesised that the higher frequency of transition SNPs than transversion SNPs is likely to contribute to conservation of protein structure and RNA stability during evolution [48]. Among transitions, C/T SNPs appeared to be more abundant than A/G SNPs. This is comparable with the previous findings in monocots [41,46,49]. On the other hand, in agreement with previous reports on the occurrence of transversions, the frequency of T/A transversion SNPs in Godawee was higher than that of A/C, G/T and C/G transversion SNPs [42,46].

Plant salinity tolerance occurs in two phases known as osmotic and ionic. The osmotic phase starts with an increase in salt concentration around the roots and is characterised by reduced rate of shoot growth and reduction in number of tillers. Ionic phase starts with the accumulation of salts above the toxic levels in old leaves and is characterised by the death of leaves [50]. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants can be categorised as (1) ion homeostasis and compartmentalization, (2) ion transport and uptake, (3) biosynthesis of osmoprotectants and compatible solutes, (4) activation of antioxidant enzyme and synthesis of antioxidant compounds, (5) synthesis of polyamines, (6) generation of nitric oxide (NO), and (7) hormone modulation and involved several pathways [51]. The STRGs that were identified for this investigation are involved in these mechanisms.

Analysis of the variants in the 28 STRGs in Godawee showed that all were polymorphic. Among the 2881 variants identified in STRGs, 2723 variants were found to be in non-coding regions, whereas 158 were in the coding regions. In order to predict the nature of selection on individual genes, the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous SNPs (Ka/Ks ratio) was calculated for each gene [52]. The results showed that OsAPx8, OsHKT1;1, OsNAC and OsPSY1 genes were under neutral conditions of evolution in Godawee. Several other STRGs were found to be still evolving under positive or negative selection. The most significant of all the STRGs was the highly polymorphic OsHKT2;1 gene (32, non-synonymous and 36 synonymous SNPs). OsHKT2;1 gene encodes a Na+/K+ transporter, a key component in Na+ efflux from roots and a major contributor to salinity tolerance in plants [53]. The highly polymorphic nature of this gene suggest that it could be playing a major role in salinity tolerance of Godawee. Two SNPs, the 1312T>C SNP of the HKT2;1 gene that results in the substitution of the amino acid Phenylalanine by Leucine at position 438 in the HKT2;1 protein and the 470T>C SNP of the HKT2;3 gene that results in the substitution of the amino acid Isoleucine by Threonine at position 157 in HKT2;3 protein were predicted to be affecting their function by at least two function prediction algorithms. Amino acid motifs in conserved regions are known to be vital for protein function and stability [34,54]. In addition to these two SNPs detailed analysis of all 28 STRGs to understand the genetic basis of salinity tolerance of Godawee resulted in the identification of 14 additional non-synonymous SNPs that were predicted to disrupt protein function by at least one function prediction algorithm. In the absence of comparative information on deleterious nonsynonymous SNPs in other rice genomes however it is not possible to infer whether these are located in conserved regions or not.

In silico analysis of CAREs of STRGs was carried out to determine the regulatory differences in Godawee genome as compared to the reference. Cis-acting element involved in WRKY encoded transcriptional repression of the gibberellin signalling pathway in aleurone cells were observed in multiple copies in the upstream regions of all 28 genes which were functionally related to abiotic stress inducible gene expression [40]. The copy number of the WRKY cisacting elements in the upstream region of OsAPx8 (Ascorbate peroxidase 8) gene in the Godawee genome as compared to the reference was significantly high depicting the possible upregulation of OsAPx8 gene expression in Godawee. This is comparable with the previous findings where Hong and Kao [55] showed that the expression of OsAPx8 is enhanced by the accumulation of ABA (Abscisic acid) which in turn enhances the expression of WRKY transcription factors [56]. Additionally, higher numbers of WRKY cisacting elements were also observed in OsMSR2, OsTIR1, OsHKT2;3, OsHKT1;4 and OsSOS1 genes compared to their counterparts in the reference genome.

Conclusions

Sequencing and whole genome analysis of the Godawee genome has provided insights to the possible genetic basis of its salinity tolerance which is a complex trait involving multiple factors. Performing functional analysis and investigating crystal structures of the proteins is important in order to relate these SNPs and in silico functional predictions on salinity tolerance of Godawee. Furthermore, the effect of cis-acting elements (CARE) on the regulation of STRGs of Godawee should also be functionally characterised. These would be the future focuses of this research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Amita Bentota and Dr. Kapila Udawela at the Rice Research and Development Institute of Sri Lanka (RRDI), Batalagoda, Sri Lanka for their assistance.

This project was funded by a grant from John Keells Holdings, Sri Lanka.

Author Contributions Statements

The researchers involved in this project belonged to the Synthetic Biology Group of the Human Genetics Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo (Sanjeewa Singhabahu, Chathura Wijesinghe Dilini Gunawardana and Vajira H. W. Dissanayake) and John Keells Research, Colombo (Muditha Senerath Yapa, Madushani Kannangara, and Roshani Edirisinghe). The idea to sequence the Godawee Genome was conceived by the two groups during their monthly research discussions. The team at the Human Genetics Unit designed the study, carried out the experiments, performed bioinformatics analysis, and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to critical review and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Kovach MJ, Sweeney MT, McCouch SR (2007) New insights into the history of rice domestication. Trends Genet 23: 578-587.

- Khush GS (1997) Origin, dispersal, cultivation and variation of rice. Plant MolBiol 35: 25-34.

- UNFPA (2014) Linking Population, Poverty and Development.

- Eckardt NA (2009) The Future of Science: food and Water for Life. Plant Cell 21: 368-372.

- FAO (2009) Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security.

- UN-Water Annual Report (2012).

- Cominelli E, Conti L, Tonelli C, Galbiati M (2013) Challenges and perspectives to improve crop drought and salinity tolerance. N Biotechnol 30: 355-361.

- Munns R, Turkan I (2011) Plant Adaptations to Salt and Water Stress. Differences and Commonalities. Adv Bot Resea 57: 555.

- Rengasamy P (2006) World salinization with emphasis on Australia. J Exp Bot 57: 1017-1023.

- United States Salinity Laboratory Staff (2016) Diagnosis and improvement of saline and alkali soils. US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Handbook No. 60.

- Lennard BG (2003) The interaction between waterlogging and salinity in higher plants: causes, consequences and implications. Plant and Soil 253: 35-54.

- Munns R (2002) Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ 25: 239-250.

- USDA Bibliography on Salt Tolerance (2013) Fibres, Grains and Special Crops. Riverside, CA: George E. Brown, Jr. Salinity Lab. US Department Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service.

- Eynard A, Lal R, Wiebe K (2005) Crop response in salt-affected soils. J Sustain Agr 27: 5-50.

- Gao JP, Chao DY, Lin HX (2007) Understanding Abiotic Stress Tolerance Mechanisms: Recent Studies on Stress Response in Rice. J Integrative Plant Biol49: 742−750.

- Lafitte HR, Ismail A, Bennett J (2004) Abiotic stress tolerance in rice for Asia: progress and future. 1–17 in Proceedings of the 4th International Crop Science Congress, Brisbane Australia.

- Flowers TJ, Koyama ML, Flowers SA, ChinthaSudhakar KP, Shing KP, et al (2000) QTL: their place in engineering tolerance of rice to salinity. J Exp Bot51: 99-106.

- Koyama ML, Levesley A, Koebner RMD, Flowers TJ, Yeo AR (2001) Quantitative trait loci for component physiological traits determining salt tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol 125: 406-422.

- Bhatnagar-Mathur P, Vadez V, Sharma KK (2008) Transgenic approaches for abiotic stress tolerance in plants: retrospect and prospects. Plant Cell Rep27: 411-424.

- Blumwald E, Grover A (2006) Salt Tolerance.Plant Biotechnology: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd;206-224.

- Munns R (2005) Genes and salt tolerance: bringing them together. New Phytol167: 645-663.

- Borsani O, Valupuesta V, Botella MA (2003) Developing salt tolerant plants in a new century: a molecular Biology approach. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 73: 101-115.

- Nielsen R, Paul JS, Albrechtsen A, Song YS (2011) Genotype and SNP calling from next-generation sequencing data. Nat Rev Genet12: 443-451.

- De Costa WAJM, Wijeratne MAD, De Costa DM (2012) Identification of Sri Lankan rice varieties having osmotic and ionic stress tolerance during the first phase of salinity stress. Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka.40: 251-280.

- Plant Genetic Resources Centre (PGRC) (1999) Characterization Catalogue of Rice (Oryzasativa) germplasm. Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture and Lands, Sri Lanka.

- Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics25: 1754-1760.

- Simpson JT, Wong K, Jackman SD, Schein JE, Jones SJM, et al. (2009) ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res19: 1117-1123.

- Birol I, JackmanSD,Nielsen CB,Qian JQ, Varhol R,et al.(2009) De novo transcriptome assembly with ABySS. Bioinformatics25: 2872-2877.

- Conesa A, Götz S (2008) Blast2GO: A Comprehensive Suite for Functional Analysis in Plant Genomics. International Journal of Plant Genomics.2008: 619832.

- Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, et al. (2005) Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics21: 3674-3676.

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, et al. (2009) The Sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics.25: 2078-2079.

- McKenna A, McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, et al. (2010) The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res20: 1297-1303.

- Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, et al. (2012) A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain; w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly6: 80-92.

- Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC (2009) Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc4: 1073-1081.

- Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP (2012) Predicting the Functional Effect of Amino Acid Substitutions and Indels. PLoS ONE.7: e46688.

- Hecht, M., Bromberg Y, Rost B (2015) Better prediction of functional effects for sequence variants. BMC Genomics16: 1-12.

- Sundar AS, Varghese SM, Shameer K, Karaba N, Udayakumar M, et al. (2008) STIF: Identification of stress-upregulated transcription factor binding sites in Arabidopsis thaliana. Bioinformation2: 431-437.

- Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, et al. (2002) PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res30: 325-327.

- Higo K,Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T (1999) Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res27: 297-300.

- Zhang Z-L, Xie Z, Zou X, Casaretto J, Ho TD, et al. (2004) A Rice WRKY Gene Encodes a Transcriptional Repressor of the Gibberellin Signaling Pathway in Aleurone Cells. Plant Physiol134: 1500-1513.

- Rathinasabapathi P, Purushothaman N, Ramprasad VL, Parani M (2015) Whole genome sequencing and analysis of Swarna, a widely cultivated indica rice variety with low glycemic index. Sci Rep5: 11303.

- Jain M, Moharana KC, Shankar R, Kumar R, Garg R (2014) Genome wide discovery of DNA polymorphisms in rice cultivars with contrasting drought and salinity stress response and their functional relevance. Plant Biotechnol J12: 253-264.

- Tang T, Lu J, Huang J, He J, McCouch SR, et al. (2006) Genomic Variation in Rice: Genesis of Highly Polymorphic Linkage Blocks during Domestication. PLoS Genet2: e199.

- Hu Y, Mao B, Peng Y, Sun Y, Pan Y, et al. (2014) Deep re-sequencing of a widely used maintainer line of hybrid rice for discovery of DNA polymorphisms and evaluation of genetic diversity. Mol Genet Genomics289: 303-315.

- Wang L, Hao L, Li X, Hu S, Ge S (2009) SNP desert of Asian cultivated rice: genomic regions under domestication. J EvolBiol22: 751-761.

- Subbaiyan GK, Waters DLE, Katiyar SK, Sadananda AR, Vaddadi S (2012) Genome-wide DNA polymorphisms in elite indica rice inbreds discovered by whole-genome sequencing. Plant Biotechnol J10: 623-634.

- Hwang SG, Hwang JG, Kim DS, Jang CS (2014) Genome-wide DNA polymorphism and transcriptome analysis of an early-maturing rice mutant. Genetica142: 73-85.

- Wakeley J (1996) The excess of transitions among nucleotide substitutions: new methods of estimating transition bias underscore its significance. Tree11: 158-162.

- Batley J, Barker G, O’Sullivan H, Edwards KJ, Edwards D (2003) Mining for single nucleotide polymorphisms and insertions ⁄deletions in maize expressed sequence tag data. Plant Physiol132: 84-91.

- Munns R, Tester M (2008) Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol59: 651-681.

- Deinlein U, Stephan AB, Horie T, Luo W, Xu G, et al (2014) Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci19: 371-379.

- Roth C, Liberles DA (2006) A systematic search for positive selection in higher plants (Embryophytes). BMC Plant Biol6: 1-11.

- Oomen RJFJ, Benito B, Sentenac H, Rodriguez-Navarro A, Talon M, et al. (2012) HKT2;2/1, a K+-permeable transporter identified in a salt-tolerant rice cultivar through surveys of natural genetic polymorphism. Plant J71: 750-762.

- Ng PC, Henikoff S (2001) Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res11: 863-874.

- Hong CY, Kao CH (2008) NaCl-induced expression of ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE 8 in roots of rice (Oryzasativa L.) seedlings is not associated with osmotic component. Plant Signal Behav3: 199-201.

- Bakshi M, Oelmüller R (2014) WRKY transcription factors:Jack of many trades in plants. Plant Signal Behav9: e27700.